“What a good artist understands is that nothing comes from nowhere.”

― Austin Kleon,

Say that thousands, maybe millions of people, had been deeply moved by a painting of Jesus. Is it ok that the image is stolen?

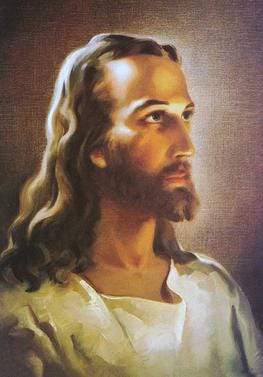

Jesus is the most portraited person in human history. You might not know the name Warner Sallman, but he popularized the stereotype of Jesus. Sallman’s Jesus is flaxen-haired with blue eyes and sharp, delicate features. The expression is one of stoic serenity or maybe resignation. It’s the face of the introvert who didn't want to come to the party and is calculating the earliest acceptable escape.

Here's Sallman’s version; it's titled Swedish-Jesus.

No, of course, it’s not called Swedish-Jesus, but, as you can tell, Sallman wasn’t particularly conscientious about ethnological accuracy. It’s not taking anything away from Sallman’s technical skill to say that he seems to be operating under the same principle as the infamous casting call for Acura’s 2012 Superbowl commercial, “Nice Looking, friendly. Not too dark.”

Get this; this picture has been reproduced literally half a billion times1. The statistical likelihood is this is the picture of Jesus that your grandparents had hanging in their hallway.

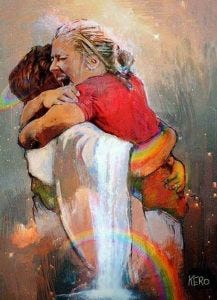

I bring this up because, in a sea of somber, Sallman-esque Jesus portraits, there are a few that rise above the tide. These images find an emotional resonance while dodging the pitfalls of the typical, well-lit, perfectly-styled, and spiritually-detached Savior. For example, below is a digital portrait of Jesus by Egyptian artist Kerolos Safwat.

Safwat’s image pictures a young, blonde woman in the arms of Jesus. She exudes irrepressible joy. Jesus is wrapping her in a huge embrace, lifting her off the ground. His face is obscured, a smart move by the artist, and it adds to the overall effect. The unconditional, life-upending, death-eradicating love that Jesus has for this nameless woman transcends the image. You feel it. You know, that’s exactly the kind of hug Jesus would give, none of that side-arm garbage.

Also, this painting has one of the best titles I’ve ever heard, When I Found the One I Love, I Held Him and Would Not Let Him Go.”2

Here’s the deal. Discovering who the artist was, took a substantial amount of internet sleuthing, a strange feature in an industry where credit is currency. In the process of trying to credit Saftwat, I stumbled right into the middle of an elaborate, complex, and ongoing moral quandary.

Maybe it’s easier just to show you.

Below is a picture of Kayla Moleschi. She’s a Canadian Rugby player. Her joy is real, and it’s definitely unbridled, but, as you can see, it’s not from jumping into the arms of Christ. Instead, she’s leaped onto her teammate, Ghislaine Landry. The elation is from the realization that they will be advancing to the Women’s Rugby Sevens Semifinals in the 2016 Olympics in Rio.

It seems that Moleschi had no idea she was in Saftwat’s painting. This particular image is copyrighted by Paige Stewart, a Toronto-based photographer. Saftwat didn’t have permission from Kayla Moleschi or Paige Stewart to use their likeness or photograph.

Alright, so it seems that Saftwat saw the unrestrained rapture on Kayla Moleschi’s face in Stewart’s photo. Saftwat, a Christian, thought that might be how someone who was reunited with Jesus would feel. You might be shrugging your shoulders, thinking, Ok, maybe the origin story of the painting isn’t very inspiring, but it still took creativity to connect the dots. That’s something, right?

But, hang on, it gets murkier.

Saftwat’s stolen image has itself been stolen and modified dozens, perhaps hundreds of times. These adapted prints are available at a wide variety of online shops. The pirated versions have been retitled First Day in Heaven and customized to show a range of people hugging Jesus. If you like, you can purchase a brunette hugging Jesus, a male hugging Jesus, or a woman of African descent hugging Jesus. There’s even a version that has elements to indicate the person being hugged identifies as LGBTQIA+. It’s just like an updated version of the old children’s Sunday School song, “…every color, shape, and size; all are precious in his eyes….” 3

In one Etsy shop, a printed blanket with a variation of Stewart/Saftwat’s picture depicting a white male jumping into Jesus’ arms has the clunky title, “First Day In Heaven Male - Kerolos I Held Him And Would Not Let Him Go Woven Throw Print Jesus”.4

Notice that the title has Saftwat’s first name, but, on the same page, in a description of the art, the Esty shop owner, John Thompson, writes,

This is a great photo reprint by an unknown professional photographer.5

So what? A compelling image gets stolen and used by a wide variety of internet opportunists. Who cares? This kind of thing happens every single day. Haven’t you ever purchased a pair of $15 Ray-bans while on a Caribbean vacation? Come on. Don’t be so naive.

Well, we haven’t even gone down the rabbit hole yet. Hold on to your pocket watches.

Paige Stewart was aware that Saftwat had “borrowed” her picture. Her image is copyrighted; she could have pursued legal action, but international copyrights are notoriously difficult to enforce, and she had resigned to let it go.

For his part, Saftwat didn’t view his adaptation as “stealing.” He claimed to be inspired by Stewart’s photograph but saw his art as different and distinct from the original. And, in his defense, either he hasn’t tried very hard to capitalize on the popularity of his art or he’s not very good at it.

Saftwat was also aware that his version had been adapted and updated. In fact, based on the popularity of the stolen variations, he has since renamed his original painting, First Day in Heaven, a regression if you ask me. By all indications, he didn’t seem to mind that his “original copy” (a fun oxymoron) had been copied until he became aware of the LGBTQIA+ version. Saftwat is part of the Egyptian Coptic Orthodox Church, which officially condemns homosexuality as a sin6. He vocalized his displeasure that his image was being used to support a lifestyle he believed was wrong.

Still following? Ok, there’s more.

Stewart, the photographer, learned that Saftwat, the artist, was upset that "his" stolen image was being used in a way that he didn't support. She said, “You can steal the image to inspire your painting, and you don’t have to credit me, but don’t spread hate about the LGBT community; that’s not cool.”

If your head is spinning, I understand. Maybe this will help.

Let’s say you have 20 bucks in your wallet. A pickpocket steals your wallet but, struck by a bolt of altruism, immediately gives all the stolen money to a homeless person. You might decide not to worry about trying to recover the money. It went to a good cause. You shrug and carry on with life.

But then imagine that the $20 is stolen from the homeless person. Amazingly, the second thief is also philanthropic but ever-so-slightly less so. They give $15 of the original $20 to three different charities. However, they hold back five bucks and use it to buy drugs. You, the original victim, might now be even more upset about the original theft, but it’s not exactly clear how to pursue a satisfying outcome.

And in our scenario, the first pickpocket (Saftwat) is the one calling the police, claiming that the stolen money was his.

Did that help clear things up? No? Well, you can see why the whole thing is a bit of a mess.

In Saftwat’s mind, it’s one thing to steal “his” art, but to use it to support a cause you’re against is too far.

In Stewart’s mind, it’s one thing to steal her photograph, but then treat it like your own while publically vocalizing disagreement for a cause you support is too far.

No one involved is currently pursuing legal action. International copyrights are nearly impossible to enforce. See, Exhibit A: Your $15 cruise-stop “Ray-Bans.” Aside from the legality, what makes this even more morally complex is that thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of people, have been inspired and comforted by Saftwat’s stolen image and its many knockoffs.

Good has been introduced into the world through the act of stealing another person’s property.

For example, I originally stumbled across the bones of this story on the blog, Flying in the Spirit. The author, Tony, lost his wife of thirty-two years to pancreatic cancer. She was a Special Needs teacher whose aim was “to be Jesus to everyone she met.” As Tony was working through his own grief, he came across Saftwat’s picture. It arrested him. He was convinced that the expression on the young woman’s face as she leaped into the arms of Jesus represented his Fiona’s face as she met her Savior.

Saftwat’s “borrowed” and altered image provided genuine comfort to a grieving husband. In his post, Tony briefly addresses the controversy, but almost in passing. Clearly, for him, the impact of the image outweighs its obscure origins.

Austin Kleon wrote, “…nothing comes from nowhere…”. What a cleverly worded truth.

Moleschi’s joy at winning her rugby match, Stewart’s photographic prowess, Safwat’s digital art skills, even the shady Etsy entrepreneurs - they all point to something greater than themselves.

To paraphrase Kleon, “everything comes from somewhere,” or, in this case, Someone.

If the sages throughout history are right, then we exist to glorify God. To paraphrase the apostle Paul, whether you play rugby, photograph athletes, or create digital art, do all to the credit (or glory) of God.

This means to credit God for everything good is to lean into our ultimate longing, which itself is a commitment to our ultimate joy.

Here’s the crazy thing about giving credit - it never diminishes the giver. We, in our insecurity and fragility, assume that if we don’t take credit, then we’ll be overlooked or unnoticed. We are worried that we won’t matter. But glory is an inexhaustible resource.

It’s crucial to point back to the people that inspire the good in the world. Saftwat, at this point, knows enough to at least credit Stewart and Moleschi, and he and the Etsy artisans should do exactly that.

But it’s also crucial to point forward to the Someone that is the ultimate source and inspiration of everything good, beautiful, and moving in the world.

Speaking of credit, I owe a debt to Wendy Manzo at The Prophetic Artist. As I attempted to research Saftwat’s painting, her blog had the only overview of the situation.

Oh, and by the way, the only way to purchase a “legitimately” stolen copy of “When I Found the One I Love, I held Him and Would not let Him go” is here. I’ll let you decide what’s right.

Lippy, Charles H. (1 January 1994). Being Religious, American Style: A History of Popular Religiosity in the United States. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 185. ISBN 9780313278952.

The title is a reference to the Song of Solomon. Setting aside the theological questions about the Song of Solomon and Jesus, it’s a good title. Song of Solomon 3:4

Scarcely had I passed them

when I found the one my heart loves.

I held him and would not let him go

till I had brought him to my mother’s house,

to the room of the one who conceived me.

Yes, yes, we all know those aren’t the original lyrics.

Not planning on linking to any of the copies of the copies.

Emphasis mine. Maybe the “unknown photographer” is a reference to Stewart? But, if I can uncover the info, this Etsy shop owner could as well.

https://egyptmigrations.com/2019/03/31/coptic-queer-stories/